Galaksija, launched in 1972, was the first mass market magazine in Yugoslavia dedicated solely to communicating subjects related to science to the reading public. Today, decades after it ceased publication, Galaksija remains a cult brand in the region. Its circulation numbers reveal the enormous appeal it had in its heyday. Galaksija sold up to eighty-five thousand copies a month in a country less than half the size of the United Kingdom where similar magazines, such as Discovery and Conquest, sold between four thousand and eighteen thousand a month and were generally considered commercial failures (Bowler 2013, 2006). Despite Galaksija's popularity and enduring appeal, its scientific content has never been analysed by evaluating what the magazine covered and how it did so.

Previous studies have made the argument that science coverage in communist countries was usually determined by the ideological function of the media and tightly controlled by the government. For example, in communist East Germany, science in the media was propagandist in the sense that it reinforced and strengthened official state ideology rather than entertained or educated (Kirpal and Ilsmann 2004; Kohring 1997; Gruhn 1979). In communist Bulgaria, media coverage of science was dependent on the policies of the ruling party (Bauer et al. 2006). During the Cold War, strong government and military patronage of science (Oreskes and Krige 2014) was prevalent and this had an impact on science communication and coverage in the media (Gregory and Miller 2000; Broks 2006), often producing an optimistic portrayal of science aimed at increasing social support for scientific enterprise (Bucchi and Trench 2014; Nelkin 1995).

Yugoslavia, governed for several decades by strongman Josip Broz Tito and his centralised Communist Party, was not under the Soviet Union's direct influence like most other countries behind the Iron Curtain. All the same, many freedoms, including media freedoms, were limited during this era. Nevertheless, Yugoslavia largely avoided the most negative elements of the Cold War by not siding with either East or West, and instead playing a leading role in establishing the Non-Aligned Movement – a political grouping of developing nations. So how did science popularisation fare in a system that rejected the bloc mentality and sought a third way through the Non-Aligned Movement? Given Yugoslavia's rejection of the capitalist West, was its coverage anchored in Soviet methods and thus similar to science media in the Eastern bloc? Or was popular science in Yugoslavia free of the ideological propaganda seen behind the Iron Curtain? To answer these questions, I analysed the magazine's content during the three years of the 1970s when it enjoyed its highest circulation (1975 to 1977).

Galaksija published a diverse range of stories from short hundred-word snippets taking up only an eighth of a page to four-page features, some of them 3,200 words long. Most articles were illustrated, and most had more than one illustration: thirty-three out of thirty-six articles in a random sample published during the relevant period featured illustrations, mostly photographs but also diagrams, cartoons, and artistic renderings. The articles are appealing, easy to read, and often intriguing. Most stories are about natural science (11) or social science and the humanities (11), followed by applied sciences and technology (8), biomedical sciences (4), and the least about environment and non-human biology (2). Individual topics within these broad categories range from the traditional knowledge of indigenous Africans, crystals behaving as fluids, and ant behaviour, to Mars and Moon exploration and teenage acne.

Some articles, such as a two-page piece on telepathy and dreams and a piece about the physiology of yogis who allegedly cheat death, wade into pseudoscientific waters. Such articles still cite research and evidence, but the evidence tends to be one-sided and doesn't include critical comments from independent experts. Indeed, this shortcoming applies to most articles. Only three articles in the sample included independent commentary from an expert who was not the source of the story, indicating a general lack of balance and objectivity. This characteristic is also evident in the sometimes overconfident and overly-specific pronouncements about the future. For example, an article about the computerisation of knowledge predicts that by 1987 there will be fully-computerised open access to all scientific research, something that has not been fully realised even today.

The articles are generally positive and optimistic about science and technology endeavour and its capacity to solve problems, but they also regularly include caveats about scientific uncertainty, noting that the nature of research is not simply one-way, unimpeded progress. This fits with the magazine's stated mission to popularise science and provide objective information that will inspire readers. An example of this approach can be found in an article about the colonisation of stars that features the assertions of experts that there will be several permanent and semi-permanent manned bases on the Moon by the year 2000, something that also did not happen. But, at the same time, it is acknowledged in the article that technology may not continue to develop at its current rate.

Unlike the lead stories in the first pages of the magazine, which often criticise capitalism and promote the virtues of Yugoslav-style socialism, most articles in the remaining pages focus on pure science and technology with little politicisation. Only the following four articles in the sample deal with topics that could be described as political or ideological in terms of promoting Yugoslav socialist ideas: "Weapons in the Hands of Yugoslav Soldiers: M-56 Automatic", "Non-Alignment: Barrier to Aggression", "Science: A factor in Societal Development", and "The Phenomenon of Multinational Companies".

Most of the stories address global issues. Many cite researchers from both the capitalist West and the Soviet Union and their topics are sourced from both the capitalist and communist worlds. Only one article in the sample covers a topic specifically and uniquely located within the Soviet Union: "The Tungus Explosion". Two other articles are partly set in the Soviet Union, but not solely. Only five are located in Yugoslavia, and four are located in the United States and Western Europe. The topics of most articles either are global or transcend the globe, dealing with space. In this way, Galaksija's coverage presents science as a global, non-polarised effort common to all humanity.

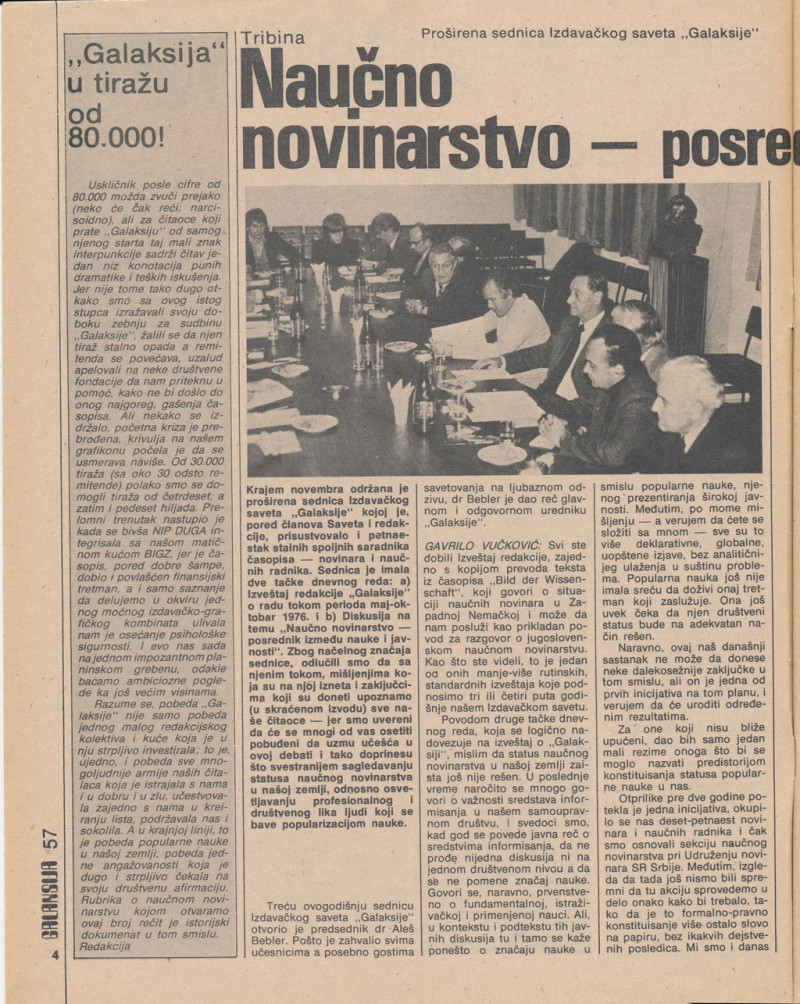

In many ways, Galaksija is similar to other popular science magazines of the twentieth century. Like its counterparts published in the United Kingdom (e.g. Conquest), it aimed to be entertaining as well as educational at a general level, featuring quizzes, competitions, and letters from readers to encourage engagement with the magazine (Bowler 2013). Like Conquest, it also reprinted articles from foreign magazines. Like the British magazines Popular Science Siftings and Tit-Bits (see Bowler 2013), Galaksija often featured short, anonymous articles without listing the source, for example in its "Interesting Science" rubric. In this rubric, themes such as mining microbes that can purify copper and the lifespans of different animals were briefly presented. Galaksija's articles were generally written or translated by science enthusiasts, including a team of science writers/journalists and editors rather than primarily by scientists. The lack of local scientists authoring articles and the magazine's subsequent reliance on foreign sources and foreign science might have been the result of the relatively weak local research environment when compared with larger and richer nations that were driving major developments such as space science. Perhaps this also explains why Galaksija was so free to engage with global science beyond the communist world. The focus on foreign science meant that local programmes and policymakers received less media scrutiny. This point was raised in an article from January 1977, Issue 57, reporting on a meeting of the magazine's editorial board in which one participant commented that the magazine did not include articles about Yugoslav research programmes and that it could address this topic critically.

Article from January 1977, reporting on a meeting of the magazine's editorial board (credit: NIP Duga, Belgrade)

Despite similarities with other popular science magazines, Galaksija was an unusual publication. Much of its content was comprised of direct translation from foreign magazines, both from the West (United States, France, and the United Kingdom) and the East (the Soviet Union). This shows that the editors and publishers had access to magazines and newspapers from both sides of the Iron Curtain as well as tacit or otherwise political permission to openly reprint foreign science content. Indeed, the editors wrote that they had subscriptions to around fifty popular science magazines from around the world and that this allowed them to feature interdisciplinary subject matter (April 1975, p. 4). In the same article, there is a reference to an influential communist official and national hero who recommended the French La Recherche as a model magazine. Clearly, science magazines published in the West were acceptable in communist Yugoslavia, even some national heroes and state officials preferring them to Soviet ones. Overall, this meant that the magazine's content was sourced more from the capitalist West than from the communist East, including socialist Yugoslavia. It also shows that, ideologically, the magazine did not embrace either the capitalist or the communist outlook but instead drew on what it saw as the most interesting ideas from both worlds. Indeed, much of its content, especially what appeared on the cover and in the lead articles, is staunchly "third-way", addressing issues such as socialism, self-management, and the Non-Aligned Movement led by Yugoslavia and its president as an alternative to either Western or Soviet world-views.

Galaksija featured little discernible pro-Soviet or communist propaganda but also no arguments against the communist system. In contrast, several articles are critical of the capitalist system. When communism and Marxism were mentioned, they were linked to the Yugoslav revolutionary fight against the Nazis during World War Two and their later co-optation into Yugoslav socialism rather than Soviet communism. Although the content was wide-ranging and gathered from both national and international sources and with no obvious ideological bent in articles that deal exclusively with science, the magazine did include political articles, many of them published in the lead pages of the magazine and highlighted on the covers. These articles generally celebrate the country's president, Marshall Tito, and his ideas about socialism, self-management, and the non-aligned movement. Tito's name and image appear frequently in the magazine, even in articles that are not specifically about him or his work.

Where did the political content and ideological position come from? Some of the articles covering news about Galaksija itself offer a hint. One piece introduces a new advisory publishing board, listing the board's members; another article summarises its discussions. The board included a colonel in the Yugoslav People's Army and a director of the state's official bulletin. Their advice, which was duly followed by the editorial team, was to include more contributions about military initiatives and developing countries. However, despite this trend toward politics and ideology on the cover and in the lead article slots, most of the rest of the roughly eighty-page magazine was dedicated to stories about science with little, if any, ideology.

The lack of emphasis on communism or the Soviet Union in Galaksija recalls Horisont, the popular Estonian science magazine established in the 1960s that covered science in a non-ideological way despite being published in a communist country (Olesk 2017). However, Galaksija, unlike Horisont which was "predominantly free of the socialist ideology", did carry some ideological content in prominent lead slots and on the cover whereas the content in the rest of the magazine was international, global, and generally free of political ideology or practical political matters of the day. Thus, the two approaches coexisted happily on the pages of the same publication.

This analysis reinforces research by science communicator Arko Olesk that suggested that science coverage in socialist countries was actually more diverse, nuanced and regionally specific than we usually give it credit for, and, indeed, that this would merit further study. Future research could, for example, provide a comparative analysis of Galaksija's content from different time periods, or could compare it with science coverage in the Yugoslav mass media which Galaksija often criticised as being lacking in both quantity and quality.

* This article is based on an academic paper published in the Journal of Science & Popular Culture.